Off-campus housing prices have climbed since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, creating fewer sales and more vacancies in Foggy Bottom and the West End, according to a report by real estate company Long and Foster last month.

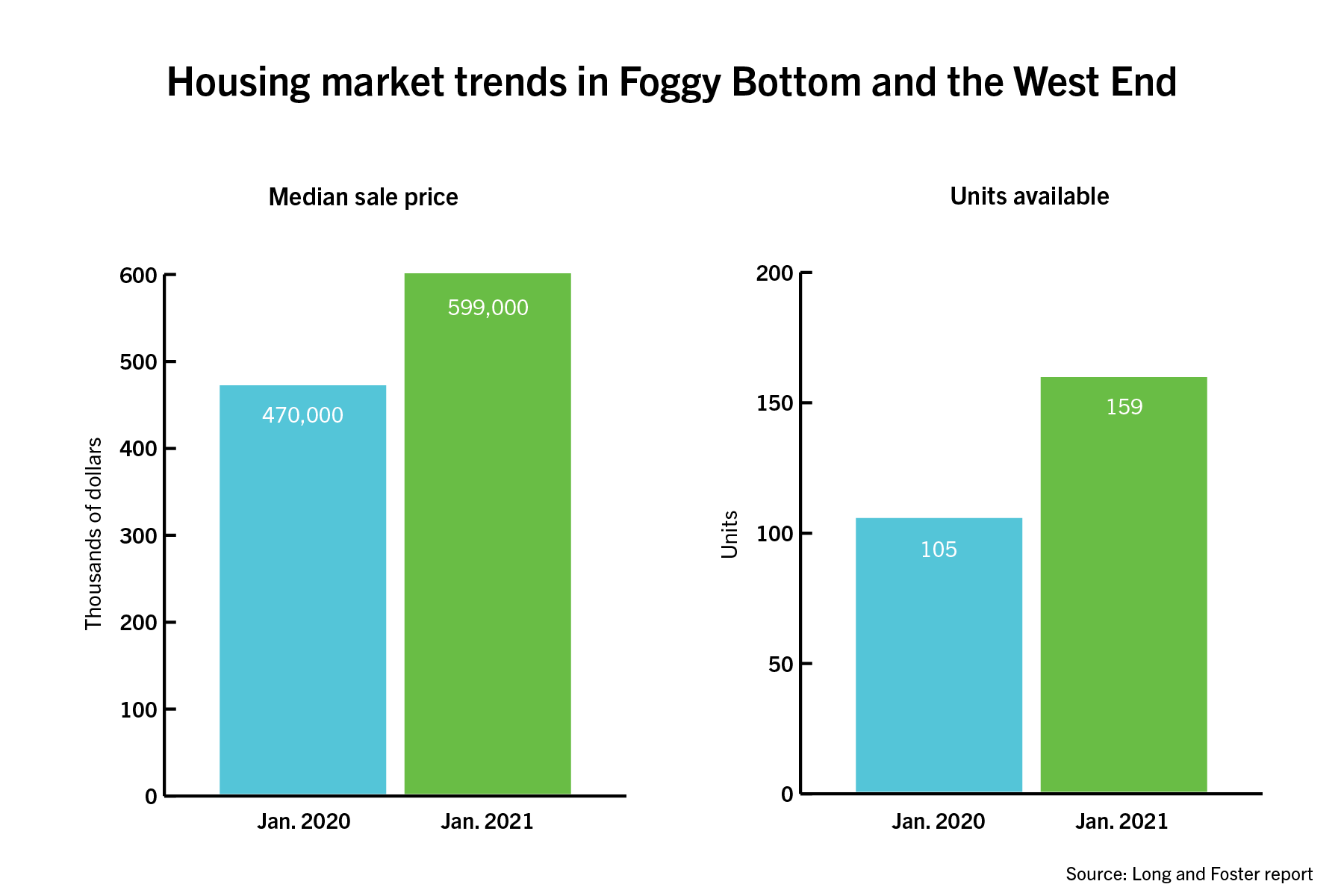

The median sale price of condominiums and cooperative housing, legal entities owning real estate, in the Foggy Bottom and West End neighborhoods spiked from about $470,000 last January to nearly $600,000, while vacancies jumped by 61 percent as of last month, the report found. Real estate experts said the trend reflects a nationwide exodus of residents from more expensive urban areas across the country during the pandemic.

Sidney Lee | Graphics Editor

Carla Labat, a managing broker for Long and Foster in Georgetown, said the dropoff in condominium sales – the most common type of unit near campus – was a result of the in-person closure of local institutions like GW, the U.S. State Department and International Monetary Fund because fewer students, federal government employees and members of the international business community are living in D.C. She said these market trends are temporary and will “rebound” once schools and businesses reopen more fully.

“The spring market is upon us, and with that, inventory is expected to expand, interest rates are expected to remain historically low for the remainder of the year and therefore savvy buyers will continue to invest in the nation’s capital and the bustling community of Foggy Bottom and West End,” she said.

The report also found “relatively few” sales in the past year, with only 21 units sold in the two neighborhoods this January after peaking at 56 sold during the height of the pandemic in May. Condominium sales across D.C. also peaked in May with 501 sales, according to another Long and Foster report on the entire District.

But the reports on D.C. at large and Foggy Bottom and the West End indicate that vacancies might start to bounce back with drops of more than 30 percent across D.C. and more than 20 percent near campus. The citywide report also found that median sale prices across the city have shot up by 9 percent, while prices near campus rose 15 percent.

Although sales in the neighborhoods were down, the price increase indicates that buyers see value in the area, Labat said.

“Students looking to rent from private owners should find a number of properties available at all price ranges for consideration after several months of units sitting empty,” she said.

A February report by Yardi Matrix, a real estate tracker, analyzed GW’s off-campus housing market, finding that the area near campus saw one of the sharpest drops in rent among all campus neighborhoods in the United States since in-person instruction was canceled last year. But the study predicted those trends would reverse ahead of the fall semester with expanded vaccinations and a possible return to some form of in-person learning.

University President Thomas LeBlanc said officials are planning to reopen to the “fullest extent possible” this fall, and vaccination speeds will ultimately influence the level of in-person activity.

Elaine Worzala, the chair of GW’s Center for Real Estate and Urban Analysis, said the best way to analyze real estate trends in a market is to look at micro markets, smaller neighborhood markets like Foggy Bottom. She said the trends in Long and Foster’s study are common in metropolitan areas amid the pandemic with more people moving out of the city.

“Foggy Bottom is dense,” Worzala said. “Because of COVID-19, people are starting to move out, so they are putting their houses on the market.”

Due to the pandemic, nationwide trends indicate that people are more likely to list their houses in urban areas and relocate to more rural locations with more space, bigger homes and backyards, Worzala said.

“In these big cities, they are moving out, and that would increase the supply,” she said. “Normally, you increase the supply, and what happens with prices? They should go down.”

Itzhak Ben-David, a professor of finance at The Ohio State University and the director of the OSU Center for Real Estate, said nationwide demand has surged for suburban homes and dropped for urban homes. National housing prices have also ticked up by 10 percent because of the pandemic, he said.

“This is very simple demand and supply,” Ben-David said. “It seems that in urban areas, before this pandemic, urban areas with restaurants and theaters and activity were suitable for young professionals, for raising families. Once there was a pandemic, many of these areas crumbled in their appeal.”

Ben-David said the market may compel many people to put their homes up for sale because they can ask for a “very high price,” hoping people will buy it. The units that are sold are therefore more costly, which inflates prices.

“Many sellers are just sitting on the sidelines,” he said. “Many of them don’t need to move. If they manage to sell for a high enough price, they would.”